In the vibrant discourse around sustainable building practices, a common misconception that often emerges is the presumed high cost associated with green construction. The narrative frequently suggests that implementing sustainable solutions and striving for environmental certifications inherently leads to increased project costs. However, this perspective fails to consider the complexity and subtle reality of sustainable development, which is far from a one-size-fits-all approach. The real essence of sustainability in construction is finding the most efficient and effective solution tailored to the specific needs of the project, considering factors such as the intended users, location, and available resources.

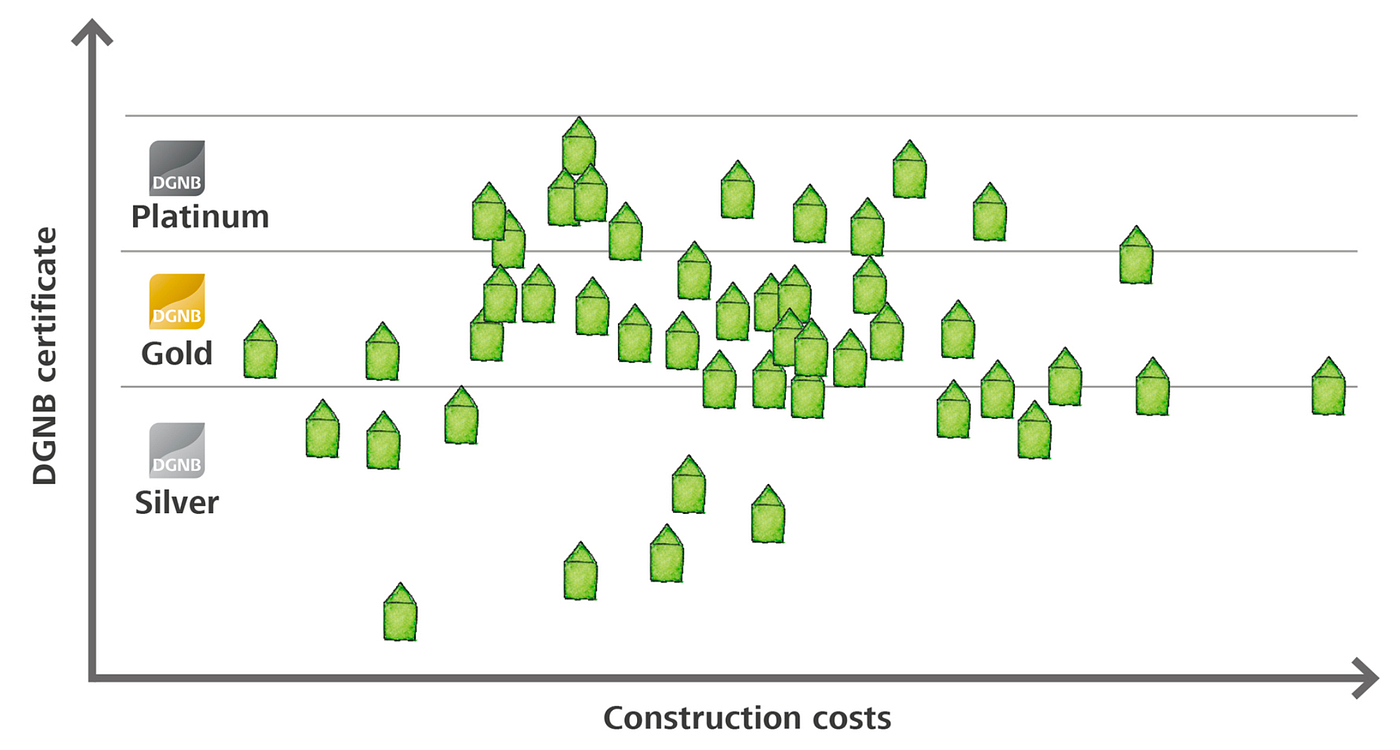

A closer examination of the data reveals a compelling counter-narrative to the myth of sustainability’s high cost. Through comprehensive analysis of construction costs versus certification levels, DGNB (DGNB is a sustainability certification, like BREEAM or LEED) carried out a study to evaluate if is was really true that the most sustainable buildings actually are the ones with highest construction costs. These were the results:

As you can observe, a clear pattern emerges that challenges the assumption that sustainability equals an increased financial burden. Contrary to expectations, projects achieving high levels of certification, such as Platinum or Gold, do not necessarily incur higher costs than their less sustainable counterparts. DGNB stated after this study that increased construction expenses often stem not from efforts to protect the climate but rather from the addition of extras designed more for enhancing marketing appeal than for necessity. The sustainable measures that actually do make the difference are planned at the early stages of the project, and thus barely impact construction costs. These findings highlight the importance of early and strategic planning, transparency in goals, and a commitment to the sustainability vision from the outset. It becomes evident that cost overruns and expensive modifications are more frequently the result of delayed decisions and changes in certification goals mid-project rather than the sustainable features themselves.

The narrative surrounding the cost of sustainability is further complicated by the industry’s relationship with spending. Often, objections to the cost of obtaining sustainability certifications like DGNB are put up against substantial investments in high-end finishes and furnishings, highlighting a misalignment in priorities. This inconsistency points out the need for a more honest conversation about the true value and affordability of sustainable building practices.

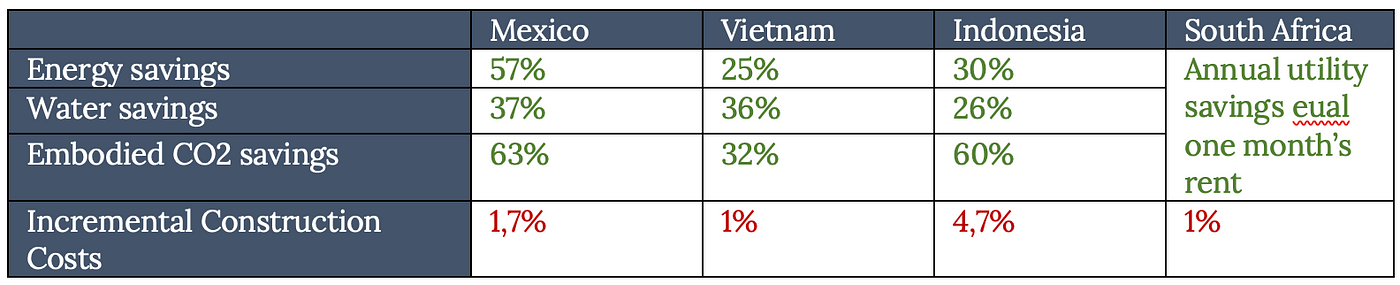

Furthermore, the IFC (International Finance Corporation) for Green Building issued a report evaluating average costs of buildings implementing sustainability measures, and their average savings in utilities. They carried out the study in a variety of cities, at different development levels, and these were the results:

Now, having the actual data on the table (literally), can we really continue to talk about an mandatory “Green Premium” in sustainable construction?

The transition towards data-driven decision-making in the construction industry is critical for breaking myths and moving beyond subjective opinions. The introduction of the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities has been a significant step in this direction, providing a framework for evaluating the sustainability credentials of building projects. For those projects already engaged in collecting data for certification purposes, aligning with the taxonomy’s criteria has proven to be straightforward, emphasizing that the perceived barriers to sustainable construction are not insurmountable. For too long our sector has gotten away knowing nothing about the data of their buildings and now the EU is pushing so that we actually do start measuring to take informed decisions.

For the last set of data, a study conducted by de GBC in Denmark involving over 200,000 houses sheds light on the energy efficiency of buildings across various certification levels. They measured the expected consumption (by energy simulation) and actual consumption of houses with different energy certifications, ranging from A through G.

In light green you have the real consumption and in dark green the simulated consumption. The findings highlight the discrepancy between expected and actual energy consumption, revealing that buildings with the lowest energy efficiency ratings do not necessarily consume more energy than anticipated. This discrepancy suggests that occupant behavior plays a crucial role in a building’s energy use. We can also appreciate that the most energy-efficient houses aren’t being calculated properly either, highlighting the our urgent need to learn how to measure and calculate correctly. This graph challenges the notion that aggressive renovation to the highest standards is always the most effective path to sustainability. According to the dark green it would be easy to say that low certification buildings are our energetic burden but if we look at the light green, the real data, are the G buildings really all that different from As?

English architect Cedric Price has a quote that goes:

“Technology is the answer… but what was the question?”

Over the past decade, the realm of design has been fervently chasing progress and innovation, leading to a landscape filled with “modern” architecture, including glass towers powered by armies of ACs, and where budgets are readily allocated for luxurious finishes. This relentless pursuit raises a critical question: have we become so blinded with (so-called) advancement that we’ve forgotten what good architecture looks like?