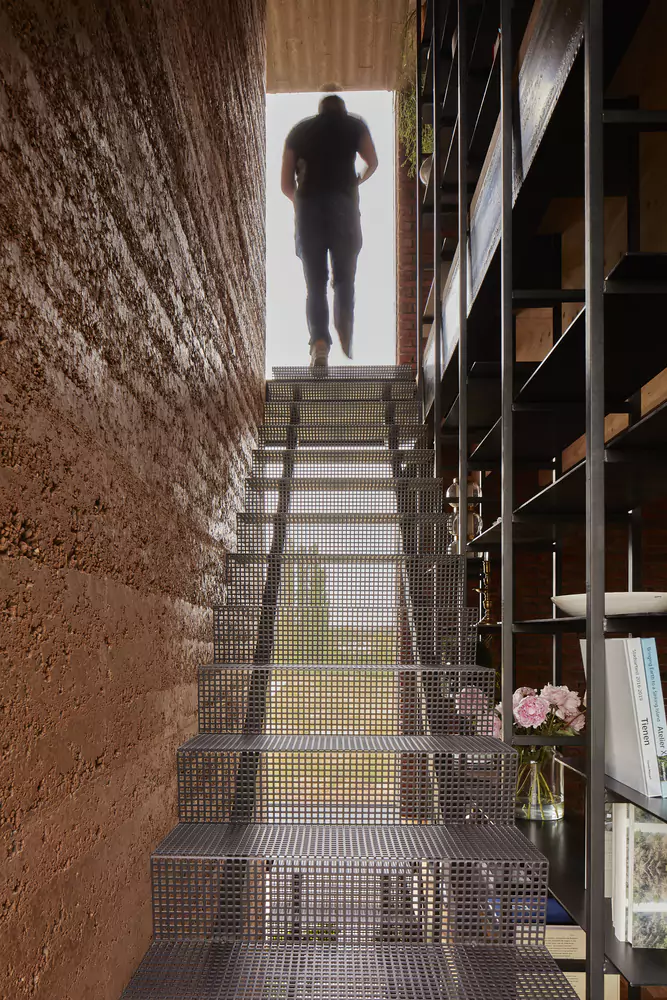

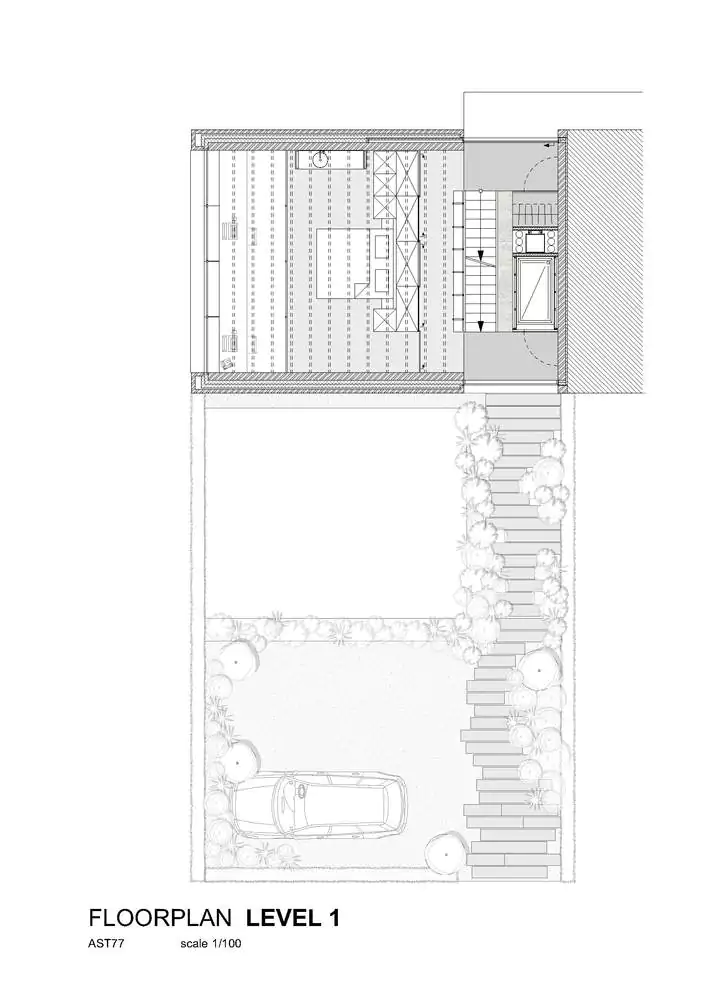

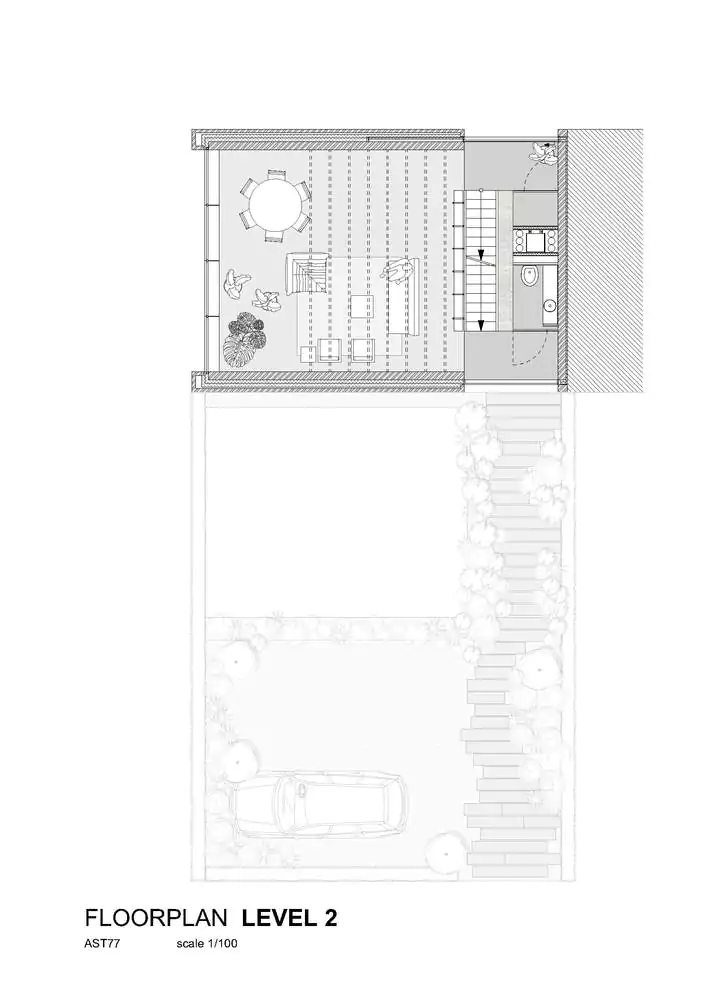

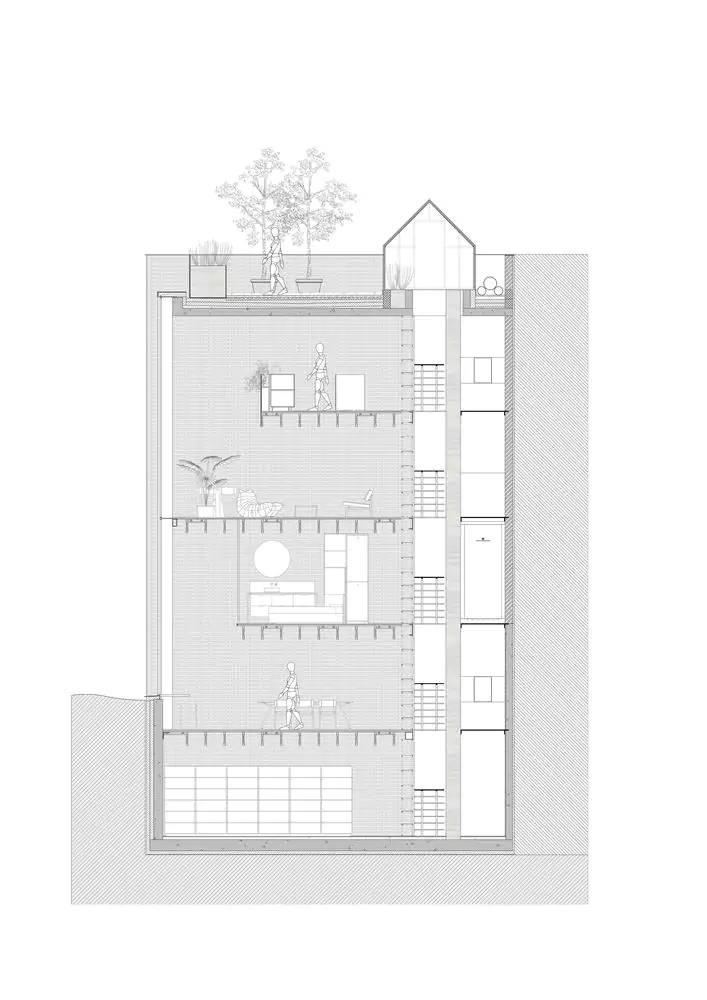

This house wasn’t name after its shape but after the concept of circular construction. One of the premises for this project was to choose and use all building materials from a circular perspective, making the whole structure an easy-to-dismount material bank. The main character of the construction is a 50cm-thick and 15m tall rammed earth wall made according to ancestral techniques (no binders or reinforcing irons) and using solely the earth dug up from the site’s excavation. The rest of the walls are 50cm-thick terracotta bricks which are joined to the main one by steel plate floors.

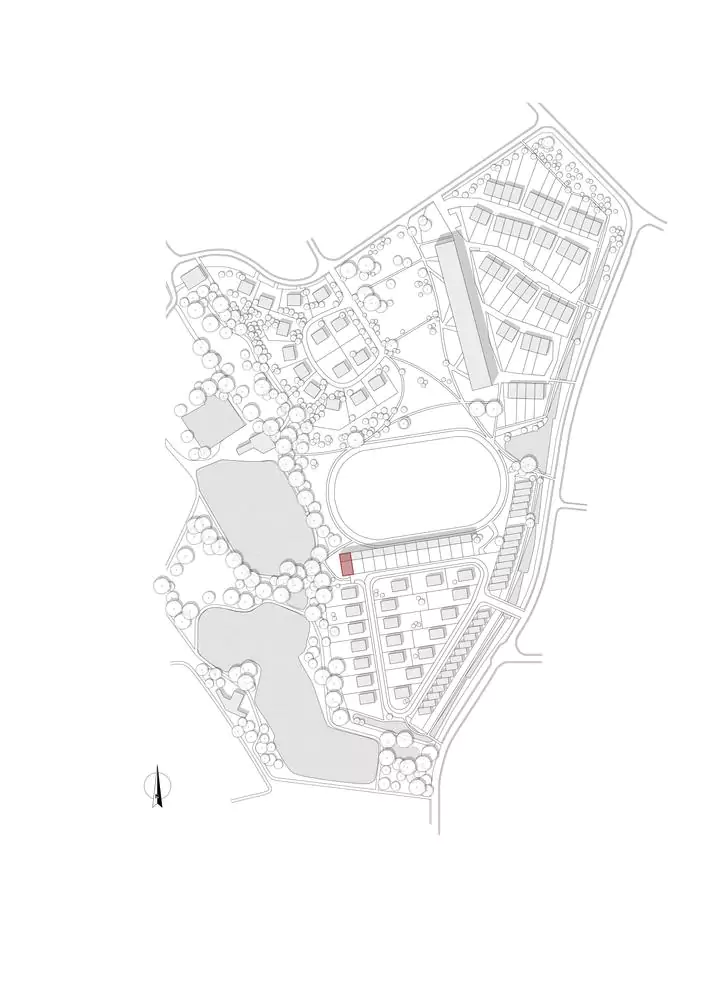

The dwelling is at the end of a row of twelve houses, which gives it a privileged view to the adjacent park but an unlucky orientation to the west. The west façade is the one to receive the last rays of sunlight and by that time of the day the building is usually already heated up because of all the solar exposure during the day. This is the reason why west façades have to be carefully treated to prevent overheating. Typical strategies are using brisesoleils, slats or minimize glazing area, but the circular brick house presents us with a dilemma as the magnificent views to the park call for a large window. The architect finally decided to go with a large glazing area but using reflective glass, which is regular glass with a metal coating that bounces off some UV and infrared light to limit the heat that enters. Additionally, this kind of glass is only see-through from the inside of the house, thus allowing nature to penetrate in the interior while providing privacy.

This house was, in fact, Peter Van Impe’s home. He was the director of AST 77 and main architect of the project. The inspiration for the circular brick house came from one of his study trips to Austria, where he discovered the work of rammed-earth specialist Martin Rauch. From then on, he sought for other rammed earth specialists to assist him in his own project. The result was this construction with a very naked materiality, where raw earth is combined with bricks, steel, concrete, glass and wood. Wet joints were used as little as possible to ensure that subsequent dismantling didn’t require a destructive approach. The idea is that, in the end, pure materials can be recovered and reused without further downcycling.

Architecture: AST 77

Location: Tienen, Belgium

Images: Steven Massart, Maarten De Bouw, Philippe Van den Panhuyzen, Thomas Noceto

Year: 2020